Table Of Content

- IAEA Publication Guides Nations on Assessing Nuclear Security Threats

- NNSA recognizes Design Basis Threat Implementation Team as 2020 Security Team of the Year

- III. Summary of Specific Changes Made to the Proposed Rule as a Result of Public Comment

- V. Guidance

- Grid Security News

- Identifying Threats in Your Design

- Group III: Out of Scope Comments

The new CAF has been used for all FOF exercises conducted after October 2004 and represents a significant improvement in ability, consistency, and effectiveness over the previous adversary forces. The final rule deletes the term “individual” to provide flexibility in defining the number of persons who may be involved in providing inside assistance. The award recognizes the contributions the members of the NNSA DBT Implementation team make each day to the nuclear security mission. The team protects some of the country’s most vital strategic assets and information, and through their award-winning work, have significantly influenced the way NNSA assesses risk and thereby made great strides in advancing U.S. national security objectives. In the past, large-scale blackouts on the electric grid have not affected an entire interconnection. Thus, system operators were able to restart generation in the blacked-out areas from external ties.[2] But as we saw from the “near miss” in the February 2021 ERCOT blackout, operators cannot count on outside assistance to restart an interconnection.

IAEA Publication Guides Nations on Assessing Nuclear Security Threats

With the expansion of nuclear and radioactive materials in use worldwide, the potential for malicious use of these materials is a growing concern. The IAEA continues to advise national authorities on best practices for nuclear security with a newly updated implementation guide — National Nuclear Security Threat Assessment, Design Basis Threats and Representative Threat Statements. It is part of the IAEA’s Nuclear Security Series (NSS) and provides guidance on how countries can implement security recommendations based on their nuclear and radioactive facilities and conduct security threat assessments to thwart risks from, inter alia, terrorists, criminals and extremists. This publication provides guidance on how to develop, use and maintain a design basis threat (DBT). It is intended for decision makers from organizations with roles and responsibilities for the development, use and maintenance of the DBT.

NNSA recognizes Design Basis Threat Implementation Team as 2020 Security Team of the Year

Webinars: Nuclear Security IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency

Webinars: Nuclear Security IAEA.

Posted: Fri, 11 Sep 2020 00:19:24 GMT [source]

The determination of this environmental assessment is that there will be no significant off-site impact to the public from this action. 104–113, requires that Federal agencies use technical standards that are developed or adopted by voluntary consensus standards bodies unless using such a standard is inconsistent with applicable law or is otherwise impractical. The NRC is not aware of any voluntary consensus standard that could be used instead of the proposed Government-unique standards.

III. Summary of Specific Changes Made to the Proposed Rule as a Result of Public Comment

Under the Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 605(b)), the Commission certifies that this rule does not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities. This final rule affects only the licensing and operation of nuclear power plants and Category I fuel cycle facilities. The companies that own these plants do not fall within the scope of the definition of “small entities” set forth in the Regulatory Flexibility Act or the size standards established by the NRC (10 CFR 2.810). The NRC requires that RTR licensees have security plans and/or procedures that reflect a graded approach which considers the attractiveness of the reactor fuel as a target, and the risk of radiological release. In general, these programs include access control to the facilities, observation of activities within the facilities, and alarms or other devices to detect unauthorized presence.

The NRC continues to work with DHS and the Nuclear Energy Institute to develop and implement a security-based drill and exercise program at power reactor licensees. Tabletop drills at four power reactor sites and a facility drill were conducted successfully, and areas for improvement were identified and incorporated by the industry into draft guidelines. Over the next three years, the industry plans to conduct security-based EP drills at each power reactor licensee with an end state of the integration of security-based EP scenarios into the biennial EP exercise program. Two other commenters stated that the regulations do not reflect protections against explosive devices of considerable size, other modern weaponry, and cyber, biochemical, and other terrorist threats.

The NRC sent a copy of the environmental assessment and the proposed rule to every State Liaison Officer and requested their comments on the environmental assessment. RTS, on the other hand, could be used to develop generic, prescriptive regulatory requirements for a particular subset of lower consequence materials or facilities. The Commission has determined under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended, and the Commission's regulations in Subpart A of 10 CFR Part 51, that this rule is not a major Federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment and, therefore, an environmental impact statement is not required.

A reasonable approach in determining the threat requires making certain assumptions about these shared responsibilities. Although licensees are not required to develop protective strategies to defend against beyond-DBT events, it should not be concluded that licensees can provide no defense against those threats. The NRC has authorized the Duke Energy Corporation, owner and operator of the Catawba plant, to irradiate four fuel assemblies of Mixed-Oxide (MOX) fuel at the Catawba plant on a test basis as part of its license amendment issued on March 3, 2005. MOX fuel technically meets the criteria of a formula quantity of Strategic Special Nuclear Material, in this case plutonium, and would be subject to the DBT provisions of § 73.1(a)(2) for theft or diversion. However, the NRC staff found that MOX fuel is not attractive to potential adversaries from a theft and diversion standpoint at the reactor site due to its low plutonium concentration, composition, and form (size and weight). The MOX fuel consists of plutonium oxide particles dispersed in a ceramic matrix of depleted uranium oxide with a plutonium concentration of less than six weight percent.

Identifying Threats in Your Design

The MOX fuel assemblies are the same form as conventional fuel assemblies designed for a commercial light-water power reactor and are over 12 feet long and weigh approximately 1,500 pounds. A large quantity of MOX fuel and an elaborate extraction process would be required to yield enough material for use in an improvised nuclear device or weapon. On the “attractiveness” bases, the NRC staff found that the complete application of 10 CFR 73.45(d)(1)(iv), 73.46 (C)(1), 73.46(h)(3), 73.46(b)(3)–(b)(12), 73.46(d)(9), and 73.46(e)(3) for MOX fuel was not necessary. The staff therefore approved the exemptions requested to these regulations, finding that they were authorized by law, and will not endanger life or property or the common defense and security, and that are otherwise in the public interest. The Commission later approved this determination in an adjudicatory order issued on June 20, 2005.

Each plant was requested to consider implementation of applicable additional strategies by August 31, 2005. The NRC inspected each plant in 2005 to review their implementation of any additional mitigative measures. In addition, § 73.1(a)(1)(iii) (the land vehicle bomb provision) is similarly revised to delete the “four-wheel drive” limitation, and to add a capability that the vehicle bomb “may be coordinated with an external assault,” maximizing its destructive potential. Further, an entirely new capability has been added to the DBT involving a waterborne vehicle bomb, which also is encompassed in the coordinated attack concept. This ISC Standard defines the criteria and processes facility security professionals should use in determining a facility's security level. This standard provides an integrated, single source of physical security countermeasures and guidance on countermeasure customization for all nonmilitary federal facilities.

As stated in the response to Group III Comments No. 18 (Security of Dry Cask Storage) and 19 (Security of Spent Fuel Pools), the NRC has required that licensees take additional security and mitigating measures against a radioactive release of spent fuel. In addition to those security-related emergency planning efforts, the NRC and DHS worked together to develop and improve EP for a terrorist attack through federal initiatives such as comprehensive review programs and integrated response planning efforts. The NRC and DHS have enhanced the coordination of integrated EP programs through evaluations of licensee and State/local/tribal response capabilities, and reviews of critical infrastructure preparedness and response plans for commercial nuclear power plants. Our combined efforts have resulted in specific enhancements to security-related EP measures, and continued improvement in capabilities for licensees and off-site response organizations to respond to a wide spectrum of events.

Another commenter did not believe the proposed DBTs protected against all conceivable attacks, such as launching a large explosive device from a boat, clogging the water intakes, dropping a conventional bomb into spent fuel pools, insider sabotage, etc. Because the regulatory guides (RGs) and the ACDs are guidance documents that provide details to the licensees regarding implementation and compliance with the DBTs, these documents may be updated from time to time as a result of the NRC's periodic threat reviews. These threat reviews are performed in conjunction with the intelligence and law enforcement communities to identify changes in the threat environment which may, in turn, require adjustments of NRC security requirements. Future revisions to the ACDs would not require changes to the DBT regulations in 10 CFR 73.1, provided the changes remain within the scope of the rule text. The Commission took into account a number of issues and sources in conducting this rulemaking, which included its experience in the implementation of the DBT Orders, the issues raised in PRM–73–12, EPAct requirements, and the public comments on the proposed rule. Additionally, the Commission specifically invited public comments on how these factors should be addressed in the rule.

Thus, the airborne threat is one which is beyond what a private security force can reasonably be expected to defend against. Second, licensees have been directed to implement certain mitigative measures to limit the effects of an aircraft strike. Therefore, the Commission has denied the request of the petition PRM–73–12 regarding the inclusion of the airborne threat in the DBTs, as well as beamhenge as physical security measures. More detailed information in support of the Commission's position is provided in the comment resolutions for Factor 6, the potential for water-based and air-based threats, and Factor 9, the potential for fires, especially fires of long duration.

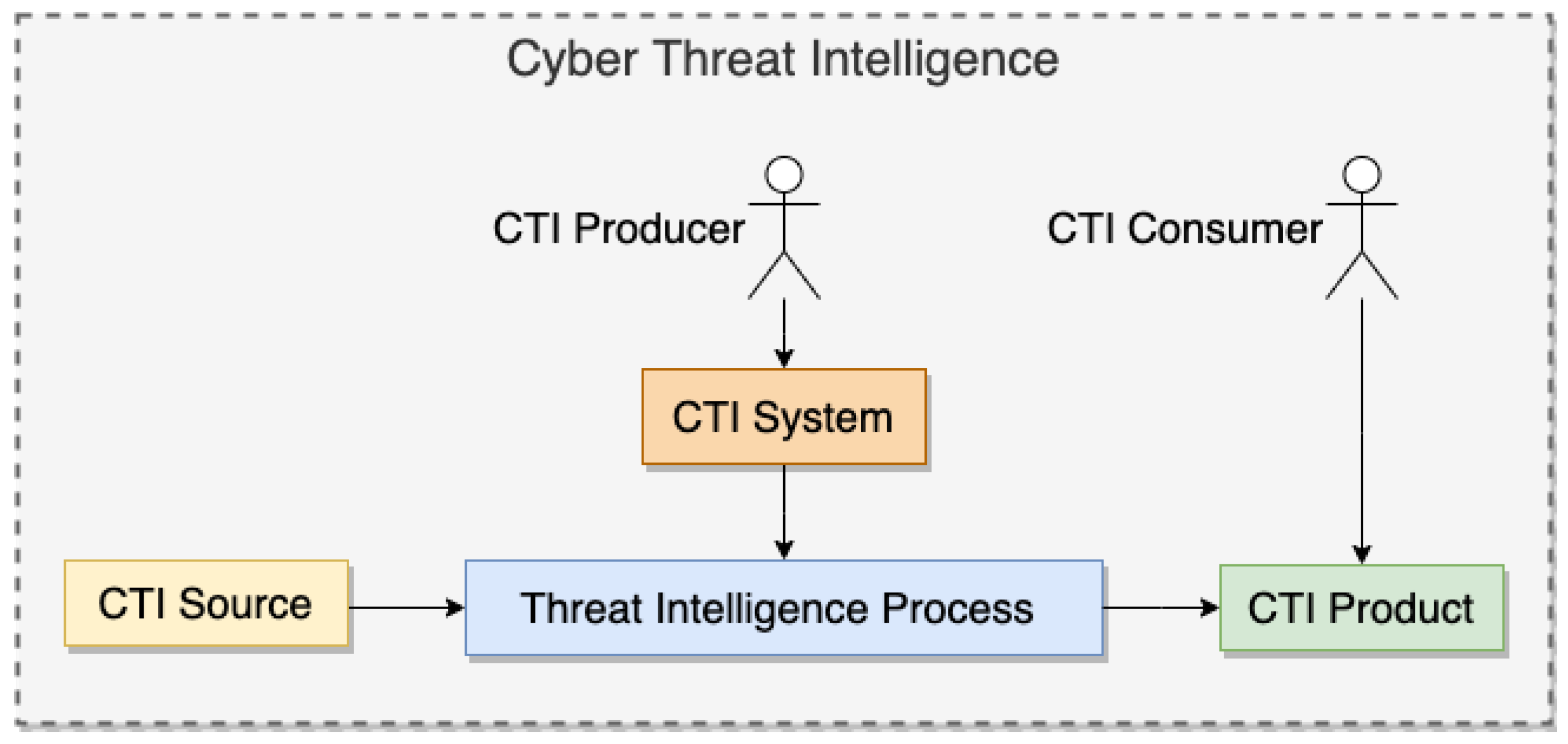

An e-learning module also exists to give participants a basic overview of nuclear security threats and risks for material and facilities, including topics such as threat assessment and planning; roles and responsibilities; coordinating assessment activities; and threat-based approaches to designing security measures. Using DBT is important because it provides detailed adversary characterizations, taking into account local threats and the specificities of a facility or activity. Such adversaries with the intention to commit sabotage and/or theft include not only external actors, but potentially also those with authorised access to facilities handling nuclear or other radioactive material. Furthermore, a DBT can be used by operators of high-risk facilities and activities to develop attack scenarios and demonstrate the effectiveness of the security systems applied. To conduct a national nuclear security threat assessment, the competent authorities collect and analyse intelligence and other threat information from open sources, past nuclear security events, other security events and other sources. They evaluate the credibility of the threat information, identify potential adversaries and their attributes and characteristics, as well as the likelihood of possible adversary actions.

Other commenters representing the nuclear industry, while agreeing that the DBT scope must be clear, asserted that the DBT can not be greater than the largest threats against which private sector facilities can reasonably be requested to defend themselves, and threats beyond the DBT are reasonably the responsibility of the national defense system. As discussed above, Section 170E of the AEA, as amended by Section 651(a) of the EPAct, directed the Commission to consider but not be limited to, the 12 factors specified in the statute in the course of the DBT rulemaking. Prior to discussing the substance of the 12 factors, the Commission notes that several commenters charged that the Commission violated Section 170E by not considering some of the 12 factors, and by deferring final consideration of some of the provisions to the final rule. Those commenters suggested that this not only violated the mandate of Section 170E, but also the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) by not providing adequate notice of the substance of the rule, and thus, the rule should be withdrawn and re-proposed. With respect to the commenter's statement on the exemptions from certain safety regulations (e.g., Appendix R fire protection standards), the NRC staff believes that the comment is out of scope of this rulemaking.

No comments:

Post a Comment